Is Northern Ontario's population aging, or is it just getting less young?

December 1, 2014 - Canada’s aging population is not a new phenomenon. The process will inevitably lead to higher pension and health care costs, as well as a smaller tax base to pay for these costs. The demographic shift will impact consumption, investments, savings, expenditures, labour, and more. Although some believe there are silver linings to all of this – such as declining labour shortages or better quality of life – the general outlook is an added strain on growth and the overall economy.

Since population aging impacts every region differently, it is important to understand what’s going on in Northern Ontario.

Looking at population projections in Figure 1 it is evident that Northern Ontario’s population is aging quicker than the province as a whole. By 2036, individuals aged 65 and older will make up almost 30% of the total population in Northern Ontario, compared with about 24% in Ontario.

Figure 1: Projected aging population as a percent of total, 2012-2036

Sources: Statistics Canada estimates, 2012, and Ontario Ministry of Finance projections, 2013.

So – why is this happening?

Aging population is being driven by three components: 1) age structure 2) natural increase and 3) migratory movements.

Age structure refers to that fact that baby boomers, who are now between the ages of 49 and 68, will continue to accelerate aging population until 2031 when the last of them turn 65[1].

The second component, natural increase, refers to the number of births minus deaths. Generally speaking, people are having less children while also living longer today than they were yesterday.

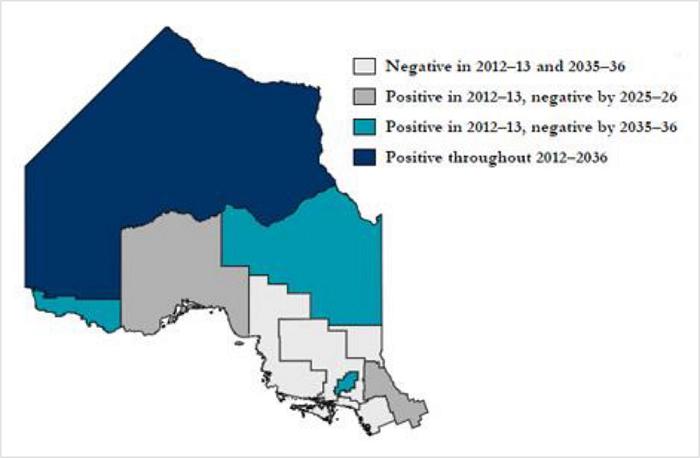

The only district in Northern Ontario that will continue to have a positive natural increase (i.e., more births than deaths) throughout 2013-2036 is Kenora (Figure 2). Since this district has the largest share of young adults in Northern Ontario, it is expected to see the most births. All other districts in Northern Ontario are projected to have more deaths than births by 2036, and in some regions this is already happening.

Figure 2: Evolution of natural increase by district, 2012-2036, Northern Ontario

Source: Screen grab from Ontario Ministry of Finance projections, 2013.

There is, however, one way to reverse these projections.

Just because a region has a relatively smaller portion of young adults to bear children, doesn’t mean that these young adults have to follow expected fertility levels from which these projections were derived. That’s right – maybe having just one more kid might not be a bad idea after all…

The second, more impactful, and less libido-driven, regional component that is affecting Northern Ontario’s aging population is migratory movements. Migration in or out of Northern Ontario can come from international, inter-provincial (between provinces) or intra-provincial (between regions within a province) sources.

In figure 3, net migration statistics were calculated in the Northeast, Northwest and Ontario, with particular focus on the most mobile age group (15 to 34 year olds). In all regions, migration among this age group is larger than all other age groups combined.

Since 2001, 15 to 34 year olds have faced negative net migration levels in the Northeast and Northwest, meaning that more individuals are going out than coming in to the region. Although there are year-to-year fluctuations, out-migration in this age group has been persistent since 2001. Today, out-migration in the Northeast and Northwest is not the highest it has ever been, however, Northern Ontario should be striving for IN-migration.

The province, on the other hand, has experienced an influx of youth and young adults since 2001. This suggests that while migration among this age cohort is flowing into the province, Northern Ontario is still experiencing a net decline.

Figure 3: Net Migration, 2001-2013

`

Source: Statistics Canada, CANSIM Table 051-0060, based on Standard Geographical Classification (SGC) 2011.

Similar to other regions, Northern Ontario’s aging population is being driven by aging baby boomers, declining fertility rates and increasing life expectancy. But, unique to the region, Northern Ontario’s aging population is being exacerbated by youth and young adult out-migration.

Some may argue that there is a silver lining to an aging population, however one which is coupled with a declining youth and young adult population raises good reason for concern.

While petitioning Northern Ontario to start having more kids is one option to help solve the structural demographic challenges, addressing the region’s migratory struggles may be a little bit more susceptible to treatment by policymakers.

[1] See: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/91-215-x/91-215-x2014000-eng.pdf

Authored by James Cuddy, Research Coordinator with Northern Policy Institute.

The content of Northern Policy Institute’s blog is for general information and use. The views expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Northern Policy Institute, its Board of Directors or its supporters. The authors take full responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of their respective blog posts. Northern Policy Institute will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information, nor will Northern Policy Institute be liable for any detriment caused from the display or use of this information. Any links to other websites do not imply endorsement, nor is Northern Policy Institute responsible for the content of the linked websites.